Information

Available via : https://melanierogergallery.com/stockroom/cameron-mclaren/

This essay discusses economies of information within the contemporary media landscape. In The New Yorker article published in 1967, Truth and Politics, Hannah Arendt stated that the mass manipulation of fact and opinion has become prevalent in the rewriting of history, in image-making, and from within government policy. Post-truth was born from a political observation, the term was first coined by Steve Tesich when he suggested that society had unreservedly decided to live in a ‘post-truth’ world in his 1992 article Government of Lies. The most well-defined characterisation or definition of post-truth would be the description of a circumstance where arguments are formed based on people's beliefs and emotions, rather than on facts. This definition also clarifies why the news media is intrinsically connected to post-truth. News has become akin to entertainment media; capitalising on people's emotions is unquestionably profitable. Through my research, I have observed how a complex state of misperception is propelled by institutional and corporate deceptiveness. This is an integration, a public-private collaboration that has the potential to offer a system driven by financial precedence; generating ethical dilemmas and deepening a sense of scepticism across the social order. Big tech, the government, and the mainstream media (MSM) are at the centre of this conversation.

To begin with, I will present research which discusses the funding of the mainstream media in Aotearoa, New Zealand today. This opening section will demonstrate how news media has become a tool for information manipulation. I make reference to official government documents and discuss the media's reliance on advertising revenue. I seek to address a central question: why has our confidence in editorial news and mainstream media declined so dramatically in recent years? And within this decline, has the industry's commitment to represent our pool of knowledge reduced in quality and traditional values? In 1961, Rupert Murdoch stated “Unless we can return to the principles of public service we will lose our claim to be the fourth estate. What right have we to speak in the public interest when, too often, we are motivated by personal gain?” With this consideration, I have explored Noam Chomsky's critical, yet accessible, theories. Chomsky has been described as a voice for the public, exposing the elite and speaking truth to power.

I persistently use the term ‘information’ throughout this text as a means to reference an exchange with the authority to inform. I also suggest that the terminology misinformation and disinformation are political in nature and are open to broad perspectives or interpretations. In this contemporary social landscape, there is undeniably too much information at hand to form an objective understanding of the ‘real’ world. So too, we are equally overloaded with both fact and fiction that inevitably blurs a concise and true perception. The condition of our information systems was undoubtedly formed through technology’s rapid development since the Industrial Revolution, alongside our unrelenting need to be perpetually informed.

There is a conflicting sense of ethical principles that exist between documentary photography and its counterparts, editorial photojournalism, and news media (information). My professional background is in editorial documentary photography. For this project, I identified and returned to this area of research after photographing the parliamentary protests in Wellington for The Washington Post in 2022. This was a critical moment in my understanding of how the mainstream media represents its people, often turning them into public castaways. I also discovered a deep concern around the use of my own photographs and how the commissioned images were used. Importantly, I found a new consideration that had eluded me throughout my career as a photographer. At this moment, I began to understand that my work was never about the presentation of reality but was solely an artistic reflection of a commodity used to sell newspapers, magazines, and related products. The photographs were purely commercial. This realisation hurt.

My studio work produced in parallel to this essay is made under the corresponding title, The Fourth Estate. The creative work finds a juncture between a state of abstraction, realism, and documentary. It also references my aforementioned apostasy. The term, fourth estate originally represented the press and news media, it emphasised the media’s independence from the government. A descriptive point of reference I will use throughout this essay is the observation that the fourth estate is a political and cultural spectacle fraught with unmeasurable influence. With this consideration, Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle is a key reference. Debord suggested that authenticity in modern society has become a representation of an illusion and that rather than speaking of the spectacle, people often prefer to use the term ‘media’. I suggest that authenticity could alternatively be referred to as truth, and illusion as untruth. Debord also critiqued post-war consumer culture, which has become even more relevant and visible than ever in 2023.

One of my key observations is that advertising and the mainstream media are dual feeders of our relentless consumerism: that the economy and our information world are forever tied. Consumerism has become so embedded in our very existence that it has become almost omnipotent (God-like). As the tangible aspects of our lives face obsolescence, a technologically-focused digital age has become like a religion or belief system. Within this belief system is a foolish contemplation that our individual principles are the most functional, the most truthful. Researchers have shown that those who think about God are more likely to accept the decision-making of artificial intelligence. I suggest that the current state of obsolescence and liberation from physical experiences has been a ruination of our broadly interconnected social values. This loss manifests as the partial removal of considered interpretation and critical thinking: our relationship to conversation and information has changed. These changes have formed an inconceivable collapse in the ongoing development of our information systems and shared knowledge.

Further, I present an exploration of contemporary photography’s connection to the concept of truth and information. To form this understanding, I have explored both historical and contemporary research in image manipulation and discuss my present concerns around technology’s interaction with image-making, and how this has affected the field of documentary photography and photojournalism. The physical expression of news media has been represented through my research around materiality, and in particular, the daily newspaper's newsprint itself. This is an integral feature of my practice. Importantly, in conjunction with materiality, is research around obsolescence and its connection to the making of my studio work; forming a direct understanding of how information has become obsolete in a post-truth world.

Economies of Information

In this section, I discuss the networks that influence our information systems with both domestic and international examples. Information: The word itself suggests fact. According to the dictionary, information represents news, facts, or knowledge. If information is factual, then it must be truthful or based upon a collective reality. However, when considering the motif of truth, we require an understanding of where we exist within each other’s reality; this could be described as truth relativity or subjectivity. The correspondence theory suggests that if we do not have an accurate understanding of reality, we are unable to speak of its truth. Conversely, we know that an accurate understanding of a singular reality is distant from an actual collective reality, it is individual and biased. It is also undoubtedly under the influence of economics.

My own photographic practice is not the only one suffering from a financial crisis of sorts. In 2017 the artist-owned agency, Magnum Photos brought in external investment into its business model, this was the first time in the agency's 70-year history. This became an example of how investment drives change in production and values. In a thoroughly corporate statement, Magnum chief executive David Kogan said, “Magnum needed to raise additional revenue to really accelerate the growth pattern”, and to crack “the fragility in Magnum’s finance”. Photographer John Vink left the agency after this external investment, stating, “There is no way I can or want to comply to the new rules. I believe it would curtail the incredible freedom I enjoy in my work.” Shortly thereafter in a 2019 press release from Magnum Photos, they proudly described the agency’s work as credible creativity:

“In line with the times, Magnum has kept pace with progress in the marketing and advertising industries, evolving to meet the needs of global clients and in response to the diversification of its talent roster. Magnum’s strength has always been credible creativity. Their services include concept & content creation as well as full campaign production, and stretches to exhibitions, books, media partnerships and editorial features on Magnum’s own digital and social media channels. Most recently this led to creating an experimental series for car giant Audi, of their new fully electric, four-wheel-drive SUV the Audi e-tron. The project has been communicated on Magnum’s editorial site as well as social media to its wide global readership and 5.2 million followers.”

This admission of commercial intent from an agency representing an ethical core of documentary photography and photojournalism confirms that the contemporary field can only be considered bilaterally, as art or commercial advertising. Both of which need to be marketable and profit-making. Because of this, I suggest that photography has no claim to the representation of reality any more than abstract painting does… Both represent truth as equally or unequally as each other, especially in a post-truth world.

Funding impacts our information systems in unintentional ways. As staff numbers decline within media institutions, journalistic values have no choice but to follow this decline. However, there is certainly a growing commitment to corporate and commercial endurance, but how does this commitment include the ongoing maintenance of our information? On August 07, 2023, The New Zealand Herald reported on a leaked email from the E tū union. A message had been sent to staff members of Stuff (the Herald’s primary competitor). The email advised of staff cuts to be expected from within Stuff operations. These reductions were to be taken from key areas of the business including digital production, senior journalists, and other areas of specialist journalism. Stuff had also recently laid off about sixteen people from its print production team. E tū threatened Stuff with legal action and said that the proposal was “another potential savage blow to the quality of the publications you work for”.

Earlier in 2023, Mediaworks, the largest domestic commercial radio network, advised its staff that up to 90 jobs might be removed from the business. Mediaworks chief executive Cam Wallace stated, “As with many businesses in New Zealand, we are not immune to the impacts of the current economic factors [including] a likely recession this year, which will see a dampening demand from advertisers across the board.” Wallace’s statement is evidence that advertising revenue directly effects the quality of information we connect with. British author and freelance journalist, Roy Greenslade, has stated “Even before social media, it was obvious that the business model underpinning newspaper publishing could not be sustained. Advertising revenue would continue to decline, and falling sales meant circulation revenue would also drop away. In such circumstances, if we wanted journalism, as distinct from newspapers, to survive, it was necessary to contemplate new forms of funding.”

Domestically, The Public Interest Journalism Fund was instituted in 2020 by the Labour Government via NZ on Air during the global COVID-19 pandemic. It was described as being a means to support a healthy democracy, as well as sustaining Aotearoa, New Zealand’s media to produce informed and engaging journalism. The $55 million NZD fund was made up of $10 million in 2020-21, $25 million in 2021-22 and $20 million in 2022-23. The funding was a drawdown from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund (CRRF). The office of the Minister for Broadcasting and Media delineated exactly how the global pandemic had increased the rate at which obsolescence was at play, noting:

“The impact of COVID-19 has exacerbated the decline of traditional commercial media models. Prior to COVID-19, rapid technological change and changing consumer behaviour was already causing financial constraints for media organisations as advertising revenues moved away from traditional media outlets towards online platforms and social media. As a result of COVID-19, further declines in advertising revenue have resulted in significant media redundancies, pay cuts and disposal of infrastructure, with further cost-cutting measures expected. Thus, COVID-19 has accelerated the need to confront the pre-existing and fundamental challenges facing the media sector. In particular, it has compressed the time available for media companies to adapt and transition to more sustainable business models that will be fit for purpose for the future media landscape.”

In this official document, the government also presented their support for a sustainable fourth estate as a central attribute to a healthy democracy, as well as stating that one benefit of the initiative will be to counter disinformation that had spread on social media. Industry experts expressed that the requirements of the fund created a perception that the media must strictly adhere to the government narrative. Another distinct problem, evidently one that presented as a strong conflict of interest or potential means of censorship, was that funding for political coverage was off-limits. Returning to Debord is timely considering these recent local events: “Never has censorship been so perfect.” Freelance journalist and former editor of The Dominion, Karl du Fresne stated, “We should be deeply suspicious of the phrase ‘public interest journalism’. It sounds harmless – indeed, positively wholesome – but it comes laden with ideology.”

Propaganda

Conspiracy theories often exist as a counter-narrative, they also exist because some truths are hidden. Veiled truths can protect government interests. An example of this materialised between the 1960s and 1970s in The United States when The Central Intelligence Agency ran Operation Mockingbird. Within this operation, the government ran surveillance on members of the press and paid journalists to publish propaganda. Domestically in June 2021 the $3.5 million NZD advertising campaign promoting the Three Waters Reform, was described as misinformation and a taxpayer-funded propaganda campaign. A representative from the Department of Internal Affairs stated, “The department is satisfied that our campaign is truthful, balanced and not misleading and that it complies with all aspects of the Advertising Standards Code.” These examples indicate a deeply entrenched relationship between the government and the mainstream media. When exploring influence in relationship to public information it would be remiss not to include discussions on propaganda. Originally the term disinformation was adapted directly from the name of the Russian KGB propaganda office, Dezinformacija, which was coined by Joseph Stalin. Propaganda is often conveyed through the mass media; it is the dissemination of information, used to influence public opinion, in particular around political contexts. Photography, iconography and art have been a tool inside the propaganda machine throughout history, especially in war times where we saw them used as a tool to enlist by propagating a feeling of guilt or cowardice, appealing to a sense of duty or country loyalty. In Manufacturing Consent, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky discuss “the mainstream media's behaviour and performance by their corporate character and integration into the political economy of the dominant economic system.” They suggest that the overall propaganda model focuses on inequality; wealth and power affect the mass media complex. Noting Chomsky:

The gap between what the majority and the prospering elite want and need has grown larger in consequence, and the challenge to the mainstream media to protect elite interests from the demands of “the great beast” has increased. The growth of inequality has itself helped the MSM meet these challenges by pushing the political system to the right and by business and the wealthy pumping greater resources into public relations, advertising, and more direct control of the media.

In 2022, Google began to advertise in The New Zealand Herald in an apparent move to help readers connect with ‘reliable information’. The concept of narrowing the internet’s information highway seemed to oppose the foundation of what online media stood for;to remove the one-way highway of the mainstream media, into a realm where everyone’s voice counted. However, this advertising suggested that the service would help people make informed decisions and that Google itself would be working closely with news organisations to represent a range of views and communities. This is an important example of a new method of funding being brought into print news media. Where once digital platforms like Facebook or Google had been the direct competition to a newspaper's revenue, it is now apparent that a form of collaboration is taking place allowing for a censorship industrial complex to develop. In fact, Google has claimed that they are one of the world’s largest financial backers of journalism, stating that “Technology companies, news organisations and governments need to collaborate to enable a strong future for journalism and quality content that doesn’t disrupt access to the open web.”

At the same time these Google advertisements began to appear in New Zealand, this ‘trustworthy’ company was fined $391.5 million USD in the United States for a breach of customer privacy in connection to advertising and location services. Attorney General, Doug Peterson said: "For years Google has prioritised profit over its users' privacy, it has been crafty and deceptive.” Similarly, in May 2023, Facebook’s parent company Meta received a record fine under the General Data Protection Regulation of €1.2 billion Euro. Once again, this was in relation to privacy concerns, specifically for violating European Union data protection rules. This ruling would affect the companies’ ability to target advertising to the European market. Meta generated a colossal revenue of almost $117 billion USD in 2022, and one could assume from this figure alone, that any substantial fines would be seen as a cost of doing business and simply be absorbed without impact. The continual torrent of fines and privacy breaches should be observed as a prompt to slow down technology’s connection to information. The obsolescence of the physical document is a despondent reminder of how we are relinquishing our privacy and in many ways our sovereignty to that of the unknown.

In June 2023, media firms prepared to announce a significant deal with Google to help fund journalism in Aotearoa, New Zealand. The outlets included Ashburton Guardian, Gisborne Herald, Mahurangi Matters/Hibiscus Matters, Otago Daily Times, Stuff, The Spinoff, and the Wairarapa Times-Age. NZME had already signed a similar deal in 2022. Caroline Rainsford, the director for Google New Zealand, said these agreements displayed Google’s continued commitment to the country's news industry, Noting Rainsford: “Many of these titles have served their communities for decades, providing vital news and information to their regions. We’re pleased to reach these agreements to help support public interest journalism in New Zealand.”

Journalists often lean on a connection to ‘experts’ in a field, especially when lacking the time or resources to fact-check the information. Journalists, even in the field of science, archetypically work without the opportunity or proficiency to check the validity of claims themselves. Alongside this obvious resourcing issue, private companies have been known to have paid ‘experts’ to create fake research to support media press releases. This is in conjunction with paid advertising campaigns to promote their products.

A critical example was in 1953 when the first connection was made between lung cancer and smoking. American researcher, Doctor Ernst Wynder published a study that linked cigarette tar to cancer in mice. The research gained widespread editorial coverage from The Readers Digest in a piece titled, Cancer by the Carton, alongside powerhouses Life Magazine and The New York Times. The spontaneous reaction from the industry was to increase their concentration of advertising often engaging professional sports people, the healthiest of public figures to promote their products. This is an example of one key birthplace of contemporary scepticism. It presented a subconscious contrast of information for those who consumed it, newspapers were a key outlet for this glamourised and clearly misleading advertisements. An infamous quote from an executive in the tobacco industry read: “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of facts’ that exist in the minds of the general public”.

When the scientific consensus confirmed that smoking unequivocally contributed to mortality, advertisements on television and radio were removed domestically in 1963. A decade later, tobacco advertising in print media was restricted to half of a newspaper page and was also banned in cinemas and on public billboards. In 1995, all tobacco advertising and sponsorship was banned domestically. Health and information systems exist conjointly. In primitive societies, the witch doctor or medicine man was the most powerful. Throughout the Middle Ages, people turned to witches' brews and potions to relieve their aches and pains. Now in the contemporary world, people inadvertently look to the media and its financial partner, the pharmaceutical industry. In the United States, pharmaceutical powerhouse Pfizer has been a significant sponsor of the news media outlets ABC, CBS, NBC, and CNN, as well the major sponsor of the 2022 Academy Awards. This financial support to the media undoubtedly should be seen as a profound conflict of interest. Pfizer also continues to be strongly involved in political lobbying.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Pfizer profited from the most lucrative medical product (Comirnaty™) in history generating $37 billion USD. Pfizer's annual revenue of $81 billion USD was more than the GDP of most countries. Throughout this time, the media continued to promote Pfizer products leaning on medical bureaucrats to give weight to the marketing. Domestically, in 2023, medical experts penned a letter to Health Minister Ayesha Verrall. Citing Doctor Samantha Murton: "For decades, doctors have been concerned that direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription medicines presents a biased, overly optimistic picture of advertised medicines and prompts patients to request treatments they do not need." In what was a seemingly contradictory position, two of the key signatories of the letter were former Prime Minister, Helen Clark and Doctor Ashley Bloomfield, who was also one of the key promoters of Pfizer products throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Forming a strange contradiction of information, a decade prior, in 2009, Pfizer Inc. and its subsidiary Pharmacia & Upjohn Company Incorporated, paid a fine of $2.3 billion USD. This settlement was the largest healthcare fraud settlement in the history of the United States Department of Justice. It was made to resolve civil and criminal liability occurring from the illegal promotion of pharmaceutical products. Another pertinent example from big pharma is the Opioid manufacturer, Purdue Pharma, who in 1996 introduced OxyContin where it was intensely marketed as a pain relief medication. The advertising was used to minimise the risk of addiction and safety concerns, an absolute tragedy and another of many examples of money influencing health and information. In 2020, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to fraud and kickback conspiracies. “Purdue admitted that it marketed and sold its dangerous opioid products to healthcare providers, even though it had reason to believe those providers were diverting them to abusers,” said Rachael A. Honig, First Assistant U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey. Purdue Pharma, which is owned by the Sackler family agreed to pay the largest ever penalty brought against a pharmaceutical manufacturer of $3.545 billion USD as well as $2 billion USD in criminal forfeiture. P.A.I.N (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) was founded by American photographer Nan Goldin and was integral in the action made against the Sackler family. The group’s activism led to the removal of the Sackler name from major museums and galleries including The Guggenheim, The Louvre, and the Tate. The Sackler family were once key figures in philanthropy to the arts, now they are synonymous with shame and misery. Noting Goldin:

“The Sacklers made their fortune promoting addiction. OxyContin is one of the most addictive painkillers in the history of pharmacology. They advertised and distributed their medication knowing all the dangers. The Sackler family and their private company, Purdue Pharma, built their empire with the lives of hundreds of thousands. The bodies are piling up. In 2015, in the US alone, more than thirty-three thousand people died from opioid overdoses, half of them from prescription opioids; 80 percent of those who use heroin or buy fentanyl on the black market began with an opioid prescription. These statistics are growing exponentially.”

The Decline

My research seeks to understand the social impact when the media and private corporations present information born from a conflict of interest. It is estimated that approximately half of the content in newspapers is repurposed from public relations activities and press releases. This leaves a big question about the potential bias or mistruths within the reporting. Citing Professor Melanie Bunce, Head of the Journalism Department at the School of Communication and Creativity at City, University of London: “The net result of growing marketing budgets, and declining journalism resources, is that the media is vulnerable to being co-opted by politicians, businesses, or others with an agenda.” When compared to the golden age of journalism, the magazine and television era of the 1950s to the mid-1970s, today's information world simply doesn’t exist at the same scale. Investigative stories were once revered and respected but have now been consistently replaced with politically charged opinion pieces. I again reflect on Debord: "In a world that really has been turned on its head, truth is a moment of falsehood.” A sense of neutrality and real-world information has largely disappeared. As well, news stories are demographically microtargeted to allow for successful political or social persuasion. Even with an understanding that journalistic voices are few, and often represent limited cultural diversity, fundamentally their words are trusted to be broadly representative, considered, reliable and honest. Throughout history, the news media has represented itself as a fearless warrior of unbiased truth. In Aotearoa, New Zealand, The motto of the Whanganui Chronicle was Verite Sans Peur, French for Truth without Fear. The Times in Hamilton also shared the same catchphrase Truth without Fear. In 1896 it was noted in The New York Times:

THE NEW-YORK TIMES give the news, all the news, in concise and attractive form, in language that is parliamentary in good society, and give it as early, if not earlier, than it can be learned through any other reliable medium; to give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of party, sect, or interests involved; to make the columns of THE NEW-YORK TIMES a forum for the consideration of all questions of public importance, and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.

In a similar way, the field of documentary photography has conventional limits. It has traditionally carried information about a group or community of the powerless to another group of the socially powerful or elite. However, in a contemporary context, this limited representation has transformed. Through the advent of the smartphone, the accessibility of the camera and lens has undoubtedly changed the photographic and journalistic landscape. Almost 7 billion people now have access to a modern camera system, a system that is capable of publishing images and video globally and instantaneously. Due to what has now been called citizen journalism, global news media finds itself one step closer to complete obsolescence. The fifth estate, a socio-cultural reference refers to groups in contemporary society, publishing information outside of the mainstream media. The most well-known voice of the fifth estate is the incarcerated founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange. In a 1969 editorial, it was stated “We believe that people who are serious in their criticism of this society and their desire to change it must involve themselves in serious revolutionary struggle.” This was published in the socially and politically radical underground newspaper, Fifth Estate founded in Detroit, in 1965 by Harvey Ovshinsky.

By 2025, it is expected that ninety percent of the world’s population will have a supercomputer in their pocket. In the same year, it is expected that ten percent of people will wear clothes connected to the Internet, ninety percent of people will have unlimited and free (advertising-supported) storage, and one trillion sensors will be connected to the internet. Undoubtedly, another example of how technologies’ connection to information is impenetrable and evolving. This technological understanding raises an important question, do documentary photographers and photojournalists simply exist as a middleman, an intermediary to information? I suggest that they do. I argue that documentary photography is no longer a representation of reality but rather a symbolic representation of artistic aesthetic intent used to give advertising a sense of legitimacy.

Another self-reflective consideration is that the process of photographic image-making has become commercially competitive, developing a harmful tone of comparison across the industry. Speaking from first-hand experience, the ubiquitous art and photography competitions that artists may feel obliged to enter are an example. Noting American artist, Martha Rosler: “Documentary fueled by the dedication to reform has shaded over into a combination of exoticism, tourism, voyeurism, psychologism and metaphysics, trophy hunting- and careerism.” With an industry so small, this competition and careerism between image makers and artists only intensifies. I look to National Geographic as an example of exoticism and obsolescence. Since 1888, the publication had been owned and operated by the National Geographic Society and was the international benchmark of documentary photography and truth values. Even with its benchmark status, there was no lack of ethical controversies. Some of these were recently addressed by Belgian photographer Max Pinckers, in his 2023 series Double Reward. Citing Pinckers: “National Geographic magazine came into existence at the height of Western European colonialism and has played a significant role in the appropriation of the non-Western world and the power over it. It depicts the Western world as dynamic, rational and progressive, and everything else as primitive, backward and unchanging.”

In 2019, National Geographic was taken over and operated by none other than the Walt Disney Company. In June 2023, National Geographic laid off the last of its staff writers and was no longer to be sold on newsstands. This was a move to focus on the digital. This takeover could be cynically viewed as corporate planned obsolescence, a term that is usually reserved for the tech industry to describe the practice of designing products to break in the short to mid-term. The removal of overheads ultimately removes the quality of work and becomes another example of how money and technology affect our access to information.

It can be tempting to be antagonistic towards the digital world and its inhabitants. An optimistic view of the internet and its social media technologies would suggest that it is breaking the corporate stranglehold on journalism. This broad scope of interaction could potentially allow for a more democratic media alongside greater access to education and healthcare services, creating increased civic participation. However, there is a strong sense of self-perpetuating confusion, noise and pollution in this landscape, it’s the material basis of our contemporary social lives. Any possible transparency becomes corrupted, and repetitive to the point where everything becomes familiar. Photography’s presence online is a mass cultural arsenal experienced in conjunction with all forms of information but I specifically contemplate the interaction between advertising, news media and art. Each generates its own impact and prejudices, creating a 24/7 echo chamber. Modern technology and social media's repetitive nature turns photography into an unwilling victim of relentless mimicry, every aspect of life merges into a common stream. As New Zealand photographer Ans Westra said, “Why take another photo?”

Within the media landscape, a brutal sense of desensitisation has been cultivated, this could be viewed through the lens of Susan Sontag’s ‘Inventory of Horror’. A key example is the public's desensitisation of conflict photography from the Middle East, in particular the mainstream media's coverage of the 2003 Iraq War. Throughout this period, stories were regularly published and retracted almost immediately. This type of information misrepresentation only adds to the uncertainty and fosters global scepticism. It also raises the question, why untruths from the media are not labelled as misinformation or disinformation? Rather, these terms seem to find representation specifically in non-mainstream, independent groups or individual voices (fifth estate). An example of a journalistic perspective conjoined with artistic intent from the Middle East was shown by British Photojournalist, Tim Hetherington, in his 2008 film and public exhibition, Sleeping Soldiers. This work presented an individual experience of war from a personal and intimate perspective, bringing a sense of truth and authenticity to the series. This type of experiential representation is rare and important in an information world controlled by corporate media.

When considering the field of contemporary documentary photography, I look beyond the conventional argument that every photographer is correspondingly an editor, and due to this, no photograph is unedited; therefore making all photographs forever biased. Rather, my interest lies in the current impact technology and mass media are having on the understanding of images, both from the perspective of the artist and the audience. The photographs in a newspaper represent the enforcement of information, and domination held over the readers. An assumption of authenticity is present; This domination is that of ideology.

Trust the System

There has always been a specific connection between photography and the idea of truth. A perception that photography was a mechanism of historical authenticity representing reality, very much in the same way that the news media represents the world's information. A simple yet real-world example of this would be the library classification of art and photography books as non-fiction. In any conversation around documentary or journalistic fields, truth has traditionally been at the forefront. However, in the contemporary sense, the reading of truth or reality may have mutated into a sense of avoidance or passive admiration.

The 2020 Reuters Digital News Report observed that out of forty countries surveyed, 38 percent of people only trusted the news ‘most of the time. The 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, provides an understanding of how trust and belief in traditional media is at an all-time low. Information has become emotional, highly politicised, and biased, creating vast division. In the Western world, the conversation around social and political division alongside its connection to media has traditionally been focused on and around American politics. However, this conversation is now very much alive in Aotearoa, New Zealand. This was very apparent throughout the 2023 elections and its post commentary in the news media and throughout social media platforms.

The Edelman research stated that 53 percent of survey participants trusted mainstream media, this showed a decline of 8 percent from the previous year. Unsurprisingly, only 35 percent of people trusted social media. Edelman CEO, Richard Edelman commented on the media landscape, stating “We’ve been lied to by those in charge, and media sources are seen as politicised and biased”. Approximately 59 percent of those surveyed believed journalists and reporters were purposely trying to mislead people by saying things they know are false; about the same number of participants believed that our government leaders were purposely trying to mislead the public. Former editor-in-chief of The Guardian, Alan Rusbridger stated, “Throughout recent centuries anyone growing up in a Western democracy had believed that it was necessary to have facts. Without facts, societies could be extremely dark places. Facts were essential to informed debates, to progress, to coherence, to justice.” In Aotearoa, New Zealand, politicians, and journalists are rated as the least trusted public figures. As proven in a Research NZ survey, 35 percent of those surveyed trusted people who work for the government, and 23 percent trusted journalists.

Reality, Fiction and Myths

Myth-busting is a term given to the process of giving debate to false information through counter-evidence-based rebuttal. There is research suggesting that myth-busting reinforces misinformation through its repetition. Therefore, this suggests it is dangerous to give research-based evidence to argue your beliefs. An audacious example of the contemporary economies of information and the complexities of the post-truth world. Fact-checkers have become a staple of contemporary online information systems. The institutions present themselves as independent truth seekers, very much like the self-representation of the media previously discussed. In fact, many of the organisations that are working in the field of fact-checking are mainstream, traditional names in journalism, some examples being, The Associated Press and Reuters. The industry has seemingly ballooned into a new type of censorship complex and again presents the vested interests of public-private collaboration. FactCheck.org has stated that they do not accept corporate funding, other than from Facebook and Google. The International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) offer signatories a badge (of honour) that they are encouraged to publish on their homepages. The IFCN primary commitments are around non-partisanship and fairness, alongside transparency of sources, funding, and methodology. In Australia, The Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) has recently been supported by Meta/Facebook to de-platform Australian journalism in relation to the recent Voice Referendum. This was in breach of the rules established by Meta founder, Mark Zuckerberg. Controversies surrounded RMIT FactLab when they were shown to be confidentially receiving up to $740,000.00 AUD annually by Meta whilst their IFCN certification had expired. This was considered to be foreign-funded censorship by local journalists.

Another example of a political and technological collaboration; Ahead of the Indian national elections in May 2019, WhatsApp (owned by Meta/Facebook) made a statement that it was working with a local start-up to classify messages sent by users. These messages were flagged as true, false, misleading, or disputed. They aimed to build a database of information to better understand misinformation. WhatsApp stated that they had begun to delete accounts and pages for inauthentic behaviour and that more collaborative efforts were required as these problems could not be solved by a single organisation. This dystopian idea of allowing a technological utopian (Meta) to decide what is appropriate behaviour is concerning and could certainly be considered political interference. HyperNormalisation, the 2016 documentary film by Adam Curtis is a contemporary continuation of Alexei Yurchak’s thinking. Yurchak, a Professor of Anthropology believed that Soviet society was always destined to fail, and to maintain the appearance of a functioning system, politicians' and citizens' delusions became a self-fulfilling prophecy; falsities were accepted as reality. In the film, Curtis claims that since the 1970s, governments, financial institutions and technological utopians have abandoned the complexities of the ‘real’ world. Instead, they intended to create a simplified ‘fake’ world. It was suggested that this new world was to be managed by major corporations and kept viable by politicians and the government. The line between reality and fiction becoming ever more blurred.

I return to thinking of the Iraq war, in the film HyperNormalisation, Curtis gives an incredible example of how the entertainment world inadvertently bonds with government policy, fuelling the military-industrial complex (and media). In 2002, both British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and American President George Bush became obsessed with destroying Iraq's President, Saddam Hussein. The head of the British Intelligence Service, MI6, advised that they had found a source that had direct access to Hussein’s chemical weapons program, which was allegedly producing VX and Sarin nerve agents (weapons of mass destruction). A later report into the Iraq war pointed out that the glass containers described by the informant were not typically used in chemical munitions, it was later inferred that the informant had obviously seen the popular Hollywood movie, The Rock, starring Sean Connery and Nicholas Cage. No weapons of mass destruction were ever found. Further considering HyperNormalisation, governments and financiers (or Hollywood) are not solely liable for the abandonment of the real world, but in fact, the news media is the most complicit. They are the voice of the spectacle. As previously discussed, this was made viable through funding, creating control of the public narrative and information. This narrative acts as an algorithm, one organised by humanity rather than that of the digital or artificial intelligence, although artificial nonetheless.

Manipulation

Impactful manipulation of images requires a level of skill to create a deception. On November 27, 1960, in France, Yves Klein produced a faux newspaper, Dimanche - Le Journal d’un seul jour. The publication was distributed throughout Paris and placed on newsstands, often sitting next to the real French newspaper Le Journal du Dimanche. The cover image, Leap into the Void was photographed by Harry Shunk and János (Jean) Kender and produced in collaboration with Klein. It portrayed an image of Klein flying through the air and was paired with a caption suggesting that he regularly practised dynamic levitation. The image was in fact a composite made by joining two negatives and was produced in the darkroom by Shunk and Kender. Very much akin to the news and entertainment world of today, Klein threatened legal action against the photographer Shunk if he were to discuss the making of the image. A contemporary example in this conversation around fabricated news and photography is the 2021 publication by Norwegian photojournalist Jonas Bendiksen, The Book of Veles published by Gost. Bendiksen starts with a question: “how long will it take before we start seeing documentary photojournalism that has no other basis in reality than the photographer’s fantasy and a powerful computer graphics card?” Six months after publication, Bendiksen revealed that all the people portrayed in the book were three-dimensionally generated models. Also, all of the text was written by artificial intelligence and yet, The Book of Veles won the 2022 World Press Photo, Europe Open Format award. Relative to my research project, Bendiksen discusses themes of misinformation in the contemporary media landscape.

On May 23, 2023, Adobe integrated Generative Artificial Intelligence into Photoshop, cementing society, information and image-making into a generalised state of abstraction. The maker only needs to type a prompt to change ‘reality’. At this moment, the photographic world was presented with a sense of personal and professional obsolescence, alongside every industry amid this technological revolution. It would be easy to suggest that in fact all human pursuits have or will rapidly become obsolete, even the academic essay. Generative technology constructed a world in distress at the implications of giving users the ability to work at the speed of their imagination. Instead of imagination, personally, it invoked a nightmare and I thought of an observation from Martha Rosler in her essay: In, around, and Afterthoughts (on documentary photography) “Documentary is a little like horror movies, putting a face on fear and transforming threat into fantasy, into imagery.” This new integration was so accessible that it immediately changed photography forever and most importantly the notion of truth in the field.

Materiality and Obsolescence

In the past decades, a downward shift in newspaper readership has been observed across the world. It is impossible to ignore the fact that printing with paper and ink is expensive, time-consuming, and not lacking environmental impact. Despite a clear shift towards an entirely digital ecosystem, international print circulation still makes up the majority of income for editorial outlets. Advertising revenue presents a similar picture as well, with a majority of income earned from print revenue. However, research suggests that total newspaper revenue will decline by -2.7 percent through to 2026. Comparatively, worldwide digital circulation is growing at around 4 percent through to 2026. Even with the growth of the digital advertising infrastructure, it has yet to make up for the revenue decline experienced within the international print sector. Historically subscriptions and contributions from readers have never been enough to fund the staff and operational costs of a news outlet. The newspaper industry would have never achieved independence from the government if it wasn’t for advertising. However, this reliance on external funding has meant that newspapers live off their advertisements, and therefore the advertisers exercise indirect censorship over the information they represent.

New Zealand Media and Entertainment (NZME), the publishing company of The New Zealand Herald has seen a decline in production of around 35 percent in the last decade. In 2023, at their Auckland print press, NZME is producing 215,000 newspapers throughout the week. Their Goss HT70 press was retrofitted in 2017 with a 61-camera system to automate registration, cut-off and colour systems. This upgrade allowed for a substantial reduction in labour costs, subsequently, a full-page advertisement in The New Zealand Herald presently costs $41,363.00.

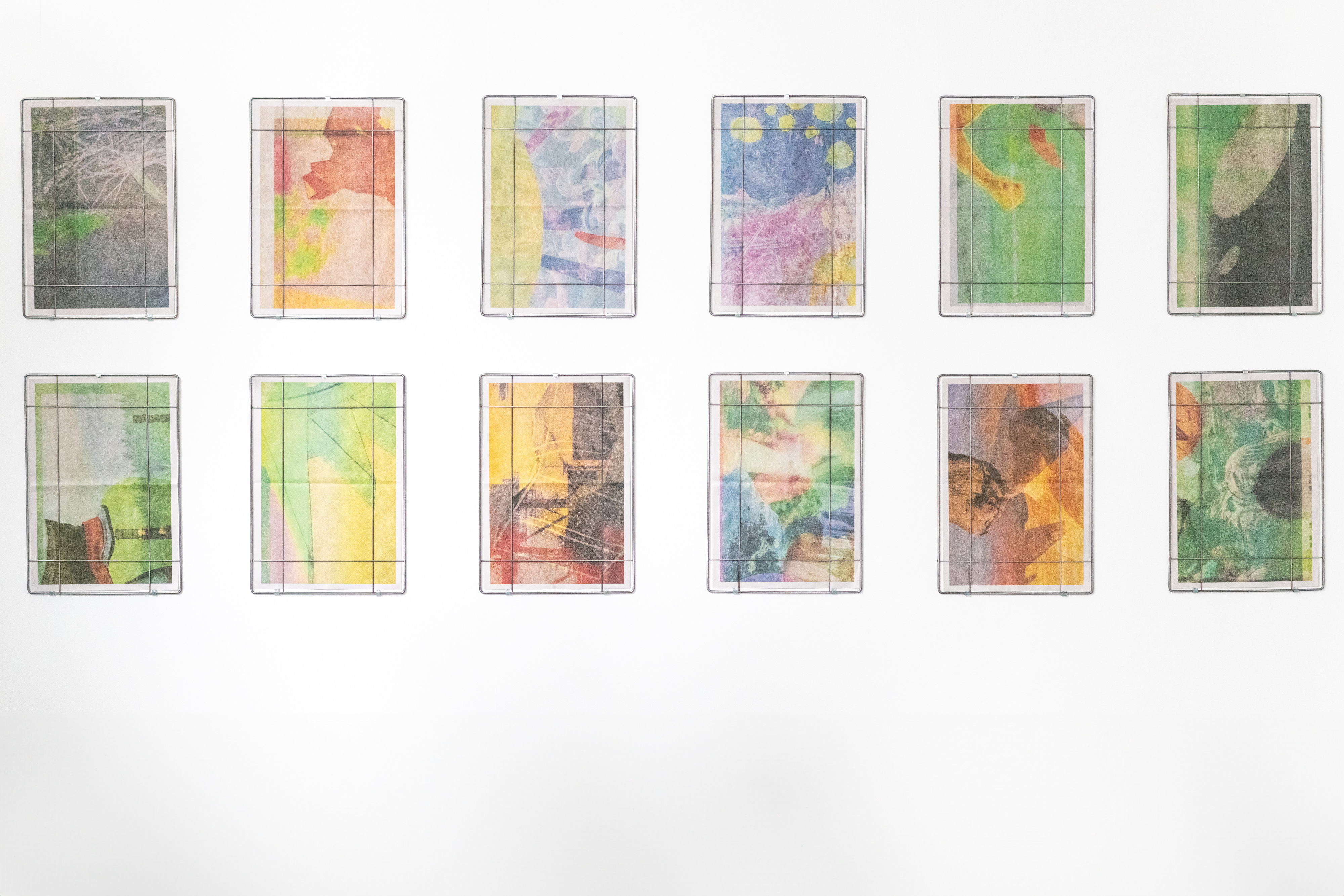

The printed photographic works in my project The Fourth Estate are titled Newspaper Photographs. This series forms a physical and literal conversation between the overlap of editorial photography and advertising in the daily newspaper, i.e. The New Zealand Herald. By illuminating the daily newspaper from below and re-photographing the translucent pages, my aim is to represent the duality of information. A representation of the post-truth era, where a new narrative is formed through the convergence of the inside and out, or the front and back. This is a permanent, indeliberate superimposition of two images. I form an intervention with my camera, a conversation between currency and information. Newspaper Photographs are abstract and degraded, seemingly corrupted both in context and presentation. They act as an anti-hero to the customary romanticism or iconography seen in contemporary photography, speaking towards the divisive force of the modern-day media. Newspaper Photographs takes inspiration in their method from the Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov’s series, Yesterday’s Sandwich. Mikhailov sandwiched two 35mm slides together creating a super-imposition, this was one of his first bodies of work, citing Mikhailov: “For me it was really important at the time as it recreates these myths or mythologems of the soviet”. Mikhailov commented that he sees Yesterday’s Sandwich as a work that celebrates beauty or the absence of beauty . In conversation with Mikhailov, my intent was to produce Newspaper Photographs as a work that observes truth or its absence of truth.

The twelve works in Newspaper Photographs interact with each other through colour, shape and materiality connecting the work to our contemporary social and geopolitical landscape. The images represent themes of climate, health, politics, protest, and war. They are hung with handmade steel frames, reminiscent of the shopfront newspaper stands from our past. The frame's materiality represents a sense of time and memory but also acts as a physical barrier between the viewer and the photographs (information). The centrality of currency and the contemporary technological marketplace has changed our connection and understanding of the information world around us. The newspaper's content and political nature alongside its specific materiality is critical in my exploration of what is a global crisis in information and influence. The process of rephotographing newspaper illustrations allows the work to move away from a singular artistic expression to a more all-encompassing social view through its connection to the public document.

The use of abstraction across the work in Newspaper Photographs could be observed as a means of diffraction. The definition of diffraction itself explains a process in which light passes through a narrow aperture and is accompanied by interference between the waves. This is evident in the printed works where an intersection exists between advertising, environmental editorial photography, and political reflections, creating a sense of intrusion, violence, and self-reflection. Newspaper Photographs were offset printed on the same Goss HT70 press as the source material, The New Zealand Herald at the NZME press plant. The works present the technical watermarks of the process with the evident pinholes and registration marks. Newspaper Photographs were also printed on the exact 40gsm newsprint manufactured by Norske Skog at their Boyer mill in Tasmania, Australia. The Boyer Mill annually produces around 261,000 tonnes of newsprint using certified plantation radiata pine. The Boyer Mill has 270 employees. This non-archival material is used in my research and speaks to obsolescence, as well as resisting the ostentatious or extravagance often witnessed in contemporary photography. The low-cost material, consisting mainly of wood pulp, also extends a conversation around economies of information. An NZME press plant employee described the newsprint as one step up from toilet paper, an entertaining description of the material that holds the world's more important information for our consumption. Domestically, in June 2021, the Tasman Mill in Kawerau was closed. The mill was also owned and operated by Norske Skog, employing 160 people and had been operating since the 1950s. It had previously been the supplier of print paper for The New Zealand Herald. Overall, the Tasman Mill produced more than 15 million tonnes of publication paper. I borrowed the technical name of the Goss Press (manufactured in Preston, England in 1993) for my video installation, HT70. This work establishes the project's overall relationship to documentary discourses and was made to be shown in proximity to Newspaper Photographs, extending the conversation between the works into the areas of time, obsolescence, consumerism and realism. HT70 fades in and out and has a duration of 44:44:04 minutes. The audio is a central attribute of the work and references an industrial echo chamber; the inescapable physical and mental noise of technology, society, and the spectacle.

As the newspaper institution fractures, along with it falls a large body of research and investigation. Newspaper journalism traditionally acted as a feeder to other forms of media, lending information to television, radio and web platforms. However, now it has become apparent that the online media feeds the newspaper, an example being The Guardian. Initially, when the web platform was launched between 1996 and 1998, the best news stories were preserved for the printed paper. As time progressed the outlet enlisted a digital-first strategy, and only the best or most attention-grabbing stories were held for print. A complete switch in polarity. As news media dies, it is being reborn simultaneously. Through my research, I observed that the world's information systems are primarily manipulated by two factors, emotion (persuasive pathos), and currency. Information has become a weapon. Imagery has the potential for misuse or weaponisation.

As reminded by Sontag: “Like a car, a camera is sold as a predatory weapon – one that’s as automated as possible, ready to spring.” There is not one field, sector or industry-leading this manipulation, but in fact, the world at large is culpable, as institutions and corporations are managed by the greed of humankind. This post-truth world is not discriminating, it is all-encompassing. Where once political bearings were a social marker, the political and social systems have continued to generate self-fulfilling contradictions: the spectacle is at once united and divided.

Referances / Bibliography

“Analysis | The Iraq War and Wmds: An Intelligence Failure or White House Spin?” The Washington Post, March 25, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/22/iraq-war-wmds-an-intelligence-failure-or-white-house-spin/.

Anders, Gunther, and Christopher John Muller. Prometheanism - Technology, Digital Culture and Human Obsolescence. Rowman & Littlefield Internati, 2016.

“Announcement: Magnum Global Ventures • Magnum Photos Magnum Photos.” Magnum Photos. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/announcement-magnum-global-ventures/.

Arendt, Hannah. Truth and Politics. The New Yorker, February 25, 1967

“Artist Nan Goldin on Addiction and Taking on the Sackler Dynasty: ‘I Wanted to Tell My Truth.’” The Guardian, December 4, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/dec/04/artist-nan-goldin-addiction-all-beauty-and-bloodshed-sackler-opioid.

Baggini, Julian. Short history of truth: Consolations for a post-truth world. Quercus, 2019.

Bate, David. Art Photography. Tate Gallery Of London (UK), 2016.

Bendiksen, Jonas. The Book of Veles. Gost Books, 2021.

Berentson-Shaw, Jess. A matter of fact: Talking truth in a post-truth world. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books Limited, 2018.

Bolton, Richard. The Contest of Meaning. Academic Press, 1990.

Bolton, Richard, and Martha Rosler. The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. The MIT Press, 1992.

Bonnett, Gillian. “Critics Say Government Three Waters Advertising Campaign Is ‘Irresponsible, Misleading.’” RNZ, October 24, 2021. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/454198/critics-say-government-three-waters-advertising-campaign-is-irresponsible-misleading.

Boykoff, Maxwell T, and Jules M Boykoff. “Balance as Bias: Global Warming and the US Prestige Press.” Global Environmental Change 14, no. 2 (2004): 125–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001.

Bunce, Melanie. The Broken Estate: Journalism and Democracy in a Post-Truth World. Bridget Williams Books, 2019.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. Langara College, 2018.

Centre, The Ethics. “Truth & Honesty - Ethics Explainer by the Ethics Centre.” THE ETHICS CENTRE, 10 Nov. 2022, https://ethics.org.au/truth-and-honesty/.

Clark, Pam. “The Future of Photoshop Is Here with Generative AI and New Innovations to Accelerate Creative Workflows.” Adobe Blog. Accessed July 6, 2023. https://blog.adobe.com/en/publish/2023/05/23/photoshop-new-features-ai-contextual-presets.

“Covid-19 New Zealand Timeline.” McGuinness Institute, 8 July 2022, https://www.mcguinnessinstitute.org/pandemic-nz/covid-19-timeline/.

Currie, Shayne. “Google, Eight NZ Media Firms Announce Major New Deals to Help Fund Journalism.” NZ Herald, June 14, 2023. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/google-major-new-zealand-media-firms-set-to-announce-major-new-deals/5AWWXBZJFFC6JGHPFKM57CRJH4/.

Currie, Shayne. “‘Savage Blow’: Stuff Faces Staff Legal Threat over Proposed New Job Cuts, amid Fears of Loss of Quality.” NZ Herald, August 6, 2023. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/media-insider-stuff-faces-staff-legal-threat-over-proposed-new-journalist-job-cuts-amid-fears-of-loss-of-quality/JCKWMNADZNG2VMEKKW4FYTUS6A/.

“Curtailing the Censorship Industrial Complex by David Randall.” NAS. Accessed October 10, 2023. https://www.nas.org/blogs/article/curtailing-the-censorship-industrial-complex.

Curtis, Adam. Hypernormalisation, 2016.

David, Marian. “The Correspondence Theory of Truth.” Oxford Handbooks Online, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557929.013.9.

Debord, Guy. Society of the Spectacle. Black and Red, 1977.

“Deep Shift: Technology Tipping Points and Societal Impact.” World Economic Forum, www.weforum.org/reports/deep-shift-technology-tipping-points-and-societal-impact. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Dunlap, David W. “1896 | ‘without Fear or Favor.’” The New York Times, August 14, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/12/insider/1896-without-fear-or-favor.html.

Dutton, William H. “The Fifth Estate Emerging through the Network of Networks.” Prometheus 27, no. 1 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020802657453.

Edelman (2021). Edelman trust barometer. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2021-trust-barometer

“Empire Calling: First World War Recruitment Posters.” Auckland War Memorial Museum. Accessed October 23, 2023. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/collections/topics/empire-calling-first-world-war-recruitment-posters.

Estrin, James. “Fact and Fiction in Modern Photography.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 24 Apr. 2015, https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/24/fact-and-fiction-in-modern-photography/.

Faking it: Manipulated photography before Photoshop. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

“Fifth Estate Records, 1967-2016 (Majority within 1982-1999).” University of Michigan Special Collections Research Center - University of Michigan Finding Aids. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://findingaids.lib.umich.edu/catalog/umich-scl-fifthestate.

F., Wood G E. The wordsmiths: A study of advertising practices in New Zealand, with particular relevance to newspaper advertising. Wellington, N.Z.: Consumer Council, 1964.

Folland, Dr. Thomas, and Dr. Thomas Folland. “Martha Rosler, the Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems.” Smarthistory, https://smarthistory.org/martha-rosler-the-bowery-in-two-inadequate-descriptive-systems/.

Fraser, T. “Phasing out of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Advertising in New Zealand.” Tobacco Control 7, no. 1 (1998): 82–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.7.1.82.

“The FSA Photographs: Information, or Propaganda?” Writing Program The FSA Photographs Information or Propaganda Comments. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.bu.edu/writingprogram/journal/past-issues/issue-1/the-fsa-photographs-information-or-propaganda/.

“Google to Pay Record $391M Privacy Settlement.” BBC News, 15 Nov. 2022, www.bbc.com/news/technology-63635380.

Goldin, Nan. “Nan Goldin.” The online edition of Artforum International Magazine, November 30, 1BC. https://www.artforum.com/print/201801/nan-goldin-73181.

Graham, Robert, and Martha Langford. Reality and Motive in Documentary Photography: Donigan Cumming = La réalité Et Le Dessein Dans La Photographie Documentaire: Donigan Cumming. Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography = Musée Canadien De La Photographie Contemporaine, 1986.

Harsin, Jayson. “Post-Truth and Critical Communication Studies.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.757.

“Has Dominic Raab Been Spreading ‘Disinformation’?” The Guardian, June 19, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jun/19/dominic-raab-disinformation.

Henriksson, Teemu. “World Press Trends Outlook: Publishers Brace for a Period Marked by Uncertainty - Wan-IFRA.” WAN, 13 Mar. 2023, https://wan-ifra.org/2023/03/world-press-trends-outlook-publishers-brace-for-a-period-marked-by-uncertainty/.

Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. London: Vintage Digital, 2010.

“History of the Guardian.” The Guardian, 11 Dec. 2017, www.theguardian.com/gnm-archive/2002/jun/06/1#:~:text=In%201994%2D95%20the%20Guardian,events%20followed%20through%201996%2D1998.

Hobbs, Mitchell. “`more Paper than Physical’.” Journal of Sociology 43, no. 3 (2007): 263–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783307080106.

“Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, Part 2.” Choice Reviews Online 50, no. 01 (2012). https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.50-0109.

Jan, NZ Herald24, and 24 Jan. “Up to 90 Jobs to Go at MediaWorks, Staff Told.” NZ Herald, January 24, 2023. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/up-to-90-jobs-to-go-at-mediaworks-staff-told-in-email-today/CW3NBWUEOZDQ3IGX5N5GDNIQAQ/.

“Journalism or Indoctrination?” NZCPR Site, www.nzcpr.com/journalism-or-indoctrination/. Accessed 18 May 2023.

KM, Karataş M Cutright. “Thinking about God Increases Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence in Decision-Making.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37549301/.

Lewandowsky, Stephan, Werner G.K. Stritzke, Klaus Oberauer, and Michael Morales. “Memory for Fact, Fiction, and Misinformation.” Psychological Science 16, no. 3 (2005): 190–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00802.x.

Lobo, F., and P. Crawford. “Time, Closed Timelike Curves and Causality.” The Nature of Time: Geometry, Physics and Perception, 2003, pp. 289–296., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0155-7_30.

McCredie, Athol. The new photography: New Zealand’s first generation contemporary photographers. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press, 2019.

Mikhailov, Boris. Yesterday's Sandwich. Phaidon, 2009.

Miller, Michael E. “New Zealand Police Battle Protesters as Tents Burn, Parliament Camp Is Cleared.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 Mar. 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/02/new-zealand-protest-parliament-police/.

Muru-Lanning, Charlotte. “What the Ashley Bloomfield Fandom Says about Us.” The Spinoff, October 7, 2021. https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/08-10-2021/what-the-ashley-bloomfield-fandom-says-about-us. xf

Myllylahti, M. & Treadwell, G. (2021). Trust in news in New Zealand. AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD). Available: https://www.aut.ac.nz/study/studyoptions/communication-studies/research/journalism,-media-and-democracy-research-centre/projects

“National Geographic Will End Newsstand Sales of Magazine next Year, Focus on Subscriptions, Digital.” AP News, June 29, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/national-geographic-layoffs-newsstand-e114363d6abb3568e02df42e14fb81b4.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andi, S. and R.K. Nielsen. Digital News Report 2020. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/DNR_2020_FINAL.pdf

“Noam Chomsky on the State-Corporate Complex: A Threat to Freedom and Survival.” YouTube, April 12, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTuawY8Qnz8.

“Norske Skog Boyer.” Norske Skog Boyer | Norske Skog. Accessed June 9, 2023. https://www.norskeskog.com/about-norske-skog/business-units/australasia/norske-skog-boyer.

“Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Fraud and Kickback Conspiracies.” Office of Public Affairs | Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Fraud and Kickback Conspiracies | United States Department of Justice, November 24, 2020. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/opioid-manufacturer-purdue-pharma-pleads-guilty-fraud-and-kickback-conspiracies.

Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Orwell, George. “‘The Dirtiest Ramp of Modern Capitalism.’” The Orwell Society, 10 Feb. 2021, orwellsociety.com/the-dirtiest-ramp-of-modern-capitalism/.

Peacock, Colin. “Mediawatch: Turning off the News?” RNZ, April 8, 2023. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/mediawatch/audio/2018885345/mediawatch-turning-off-the-news.

Peiser, Wolfram. “Cohort Replacement and the Downward Trend in Newspaper Readership.” Newspaper Research Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, 2000, pp. 11–22., https://doi.org/10.1177/073953290002100202.

Peters, Jeremy W. “Wielding Claims of 'Fake News,' Conservatives Take Aim at Mainstream Media.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Dec. 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/25/us/politics/fake-news-claims-conservatives-mainstream-media-.html.

“Pfizer Accused of Pandemic Profiteering as Profits Double.” The Guardian, February 8, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/feb/08/pfizer-covid-vaccine-pill-profits-sales.

Pinckers, Max. Double reward : Max Pinckers. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.maxpinckers.be/archive/double-reward/.

“Public Interest Journalism Fund.” Manatū Taonga - Ministry for Culture & Heritage, mch.govt.nz/media-sector-support/journalism-fund. Accessed 18 May 2023.

Rabin-Havt, Ari. Lies, incorporated: The world of post-truth politics. New York: Anchor Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2016.

Ravikumar, Sai Sachin. “WhatsApp Launches Fact-Check Service to Fight Fake News during India Polls.” Reuters, April 3, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/facebook-whatsapp-idUSKCN1RE0HD.

Rosler, Martha. Decoys and disruptions: Selected writings, 1975-2001. Cambridge, Mass, London : MIT, 2004.

Rosler, Martha. 3 works / critical essays on photography and photographs. Halifax, N.S.: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981.

Rusbridger, Alan. Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why it Matters Now, with Alan Rusbridger. Newstex, 2018. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/blogs-podcasts-websites/breaking-news-remaking-journalism-why-matters-now/docview/2252768900/se-2.

Rusbridger, Alan. Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now. Canongate, 2019.

Ruzzene, Attilia. "Causality" SAGE Research Methods Foundations, Edited by Paul Atkinson, et al. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2020. SAGE Research Methods. 21 Sep 2022, doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036916196

Satariano, Adam. “Meta Fined $1.3 Billion for Violating E.U. Data Privacy Rules.” The New York Times, 22 May 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/05/22/business/meta-facebook-eu-privacy-fine.html.

Schwab, Klaus. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Portfolio Penguin, 2017.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Photography at the Dock. University of Minnesota Press, 1991.

Smyth, Diane, Izabela Radwanska Zhang, and Ravi Ghosh. “John Vink Leaves Magnum Due to Post-Investment Contract.” 1854 Photography, June 15, 2017. https://www.1854.photography/2017/06/john-vink-leaves-magnum-due-to-post-investment-contract/#:~:text=John%20Vink%20first%20joined%20Magnum,in%20its%2070%2Dyear%20history.

Sontag, Susan. Susan Sontag on photography. London, Great Britain: Allen Lane, 1978.

Taylor, Petroc. “Smartphone Subscriptions Worldwide 2027.” Statista, 18 Jan. 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/.

Tesich, Steve. “Steve Tesich Government of Lies (Article) : Steve Tesich : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1992. https://archive.org/details/steve-tesich-government-of-lies-article.

“The Book of Veles: Magnum Photos Magnum Photos.” Magnum Photos, https://www.magnumphotos.com/arts-culture/society-arts-culture/book-veles-jonas-bendiksen-hoodwinked-photography-industry/.

“The Book of Veles.” The Book of Veles | World Press Photo, https://www.worldpressphoto.org/collection/photo-contest/2022/Jonas-Bendiksen/1.

Trust in News in New Zealand 2021 - Aut, www.aut.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/507686/Trust-in-News-in-NZ-2021-report.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Van Zee, Art. “The Promotion and Marketing of Oxycontin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy.” American journal of public health, February 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2622774/.

Wieck, Russell. Interview conducted by Cameron James McLaren. 15 May 2023.